Brain Activity During Meditation

The brain is an electrochemical organ using electromagnetic energy to function. Electrical activity emanating from the brain is displayed in the form of brainwaves.emanating from the brain is displayed in the form of brainwaves. There are four categories of these brainwaves. They range from the high amplitude, low frequency delta to the low amplitude, high frequency beta. Men, women and children of all ages experience the same characteristic brainwaves. They are consistent across cultures and country boundaries.

During meditation brain waves alter.

BETA - 13-30 cycles per second - awaking awareness, extroversion, concentration, logical thinking - active conversation. A debater would be in high beta. A person making a speech, or a teacher, or a talk show host would all be in beta when they are engaged in their work.

ALPHA - 7-13 cycles per second - relaxation times, non-arousal, meditation, hypnosis

THETA - 4-7 cycles per second - day dreaming, dreaming, creativity, meditation, paranormal phenomena, out of body experiences, ESP, shamanic journeys.

A person who is driving on a freeway, and discovers that they can't recall the last five miles, is often in a theta state - induced by the process of freeway driving. This can also occur in the shower or tub or even while shaving or brushing your hair. It is a state where tasks become so automatic that you can mentally disengage from them. The ideation that can take place during the theta state is often free flow and occurs without censorship or guilt. It is typically a very positive mental state.

DELTA - 1.5-4 or less cycles per second - deep dreamless sleep

-

Mindfulness meditation and related techniques are intended to train attention for the sake of provoking insight. Think of it as the opposite of attention deficit disorder. A wider, more flexible attention span makes it easier to be aware of a situation, easier to be objective in emotionally or morally difficult situations, and easier to achieve a state of responsive, creative awareness or "flow".

Daniel Goleman & Tara Bennett-Goleman (2001), suggest that meditation works because of the relationship between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex.Simply put, the amygdala is the part of the brain that decides if we should get angry or anxious (among other things), and the pre-frontal cortex is the part that makes us stop and think about things (it is also known as the inhibitory centre).

So, the prefrontal cortex is very good at analyzing and planning, but it takes a long time to make decisions. The amygdala, on the other hand, is simpler (and older in evolutionary terms). It makes rapid judgments about a situation and has a powerful effect on our emotions and behaviour, linked to survival needs. For example, if a human sees a lion leaping out at them, the amygdala will trigger a fight or flight response long before the prefrontal cortex responds.

But in making snap judgments, our amygdalas are prone to error, such as seeing danger where there is none. This is particularly true in contemporary society where social conflicts are far more common than encounters with predators, and a basically harmless but emotionally charged situation can trigger uncontrollable fear or anger - leading to conflict, anxiety, and stress.

Because there is roughly a quarter of a second gap between the time an event occurs and the time it takes the amygdala to react, a skilled meditator may be able to intervene before a fight or flight response takes over, and perhaps even redirect it into more constructive or positive feelings.

The different roles of the amygdala and prefrontal cortex can be easily observed under the influence of various drugs. Alcohol depresses the brain generally, but the sophisticated prefrontal cortex is more affected than less complex areas, resulting in lowered inhibitions, decreased attention span, and increased influence of emotions over behaviour. Likewise, the controversial drug ritalin has the opposite effect, because it stimulates activity in the prefrontal cortex.

Some studies of meditation have linked the practice to increased activity in the left prefrontal cortex, which is associated with concentration, planning, meta-cognition (thinking about thinking), and positive affect (good feelings). There are similar studies linking depression and anxiety with decreased activity in the same region, and/or with dominant activity in the right prefrontal cortex.

Meditation increases activity in the left prefrontal cortex, and the changes are stable over time - even if you stop meditating for a while, the effect lingers.

In the News ...

Meditation found to increase brain size PhysOrg - January 31, 2006

Meditation Shown to Light Up Brains of Buddhists Yahoo - May 2003

Using new scanning techniques, neuroscientists have discovered that certain areas of the brain light up constantly in Buddhists, which indicates positive emotions and good mood. "We can now hypothesize with some confidence that those apparently happy, calm Buddhist souls one regularly comes across in places such as Dharamsala, India, really are happy,"

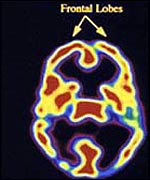

Professor Owen Flanagan, of Duke University in North Carolina, said. Dharamsala is the home base of exiled Tibetan leader the Dalai Lama. The scanning studies by scientists at the University of Wisconsin at Madison showed activity in the left prefrontal lobes of experienced Buddhist practitioners. The area is linked to positive emotions, self-control and temperament.

Other research by Paul Ekman, of the University of California San Francisco Medical Center, suggests that meditation and mindfulness can tame the amygdala, an area of the brain which is the hub of fear memory. Ekman discovered that experienced Buddhists were less likely to be shocked, flustered, surprised or as angry as other people. Flanagan believes that if the findings of the studies can be confirmed they could be of major importance. "The most reasonable hypothesis is that there is something about conscientious Buddhist practice that results in the kind of happiness we all seek," Flanagan said in a report in New Scientist magazine.

Meditation mapped in Monks - March 1, 2002 - BBC

- During meditation, people often feel a sense of no space. Scientists investigating the effect of the meditative stateon Buddhist monk's brains have found that portions ofthe organ previously active become quiet, whilst pacified areas become stimulated. Using a brain imaging technique, Dr. Newberg and his team studied a group of Tibetan Buddhist monks as they meditated for approximately one hour. When they reached a transcendental high, they were asked to pull a kite string to their right, releasing an injection of a radioactive tracer. By injecting a tiny amount of radioactive marker into the bloodstream of a deep meditator, the scientists soon saw how the dye moved to active parts of the brain.

Later, once the subjects had finished meditating, the regions were imaged and the meditation state compared with the normal waking state. The scans provided remarkable clues about what goes on in the brain during meditation. "There was an increase in activity in the front part of the brain, the area that is activated when anyone focuses attention on a particular task," Dr Newberg explained. In addition, a notable decrease in activity in the back part of the brain, or parietal lobe, recognized as the area responsible for orientation, reinforced the general suggestion that meditation leads to a lack of spatial awareness.

Dr Newberg explained: "During meditation, people have a loss of the sense of self and frequently experience a sense of no space and time and that was exactly what we saw." The complex interaction between different areas of the brain also resembles the pattern of activity that occurs during other so-called spiritual or mystical experiences.

Brain Images provide painless study

Dr Newberg's earlier studies have involved the brain activity of Franciscan nuns during a type of prayer known as "centering". As the prayer has a verbal element other parts of the brain are used but Dr Newberg also found that they, "activated the attention area of the brain, and diminished activity in the orientation area." This is not the first time that scientists have investigated spirituality. In 1998, the healing benefits of prayer were alluded to when a group of scientists in the US studied how patients with heart conditions experienced fewer complications following periods of "intercessory prayer".

And at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Boston last month, scientists from Stanford University detailed their research into the positive affects that hypnotherapy can have in helping people cope with long-term illnesses.

Scientific study of both the physical world and the inner world of human experiences are, according to Dr Newberg, equally beneficial. "When someone has a mystical experience, they perceive that sense of reality to be far greater and far clearer than our usual everyday sense of reality," he said. He added: "Since the sense of spiritual reality is more powerful and clear, perhaps that sense of reality is more accurate than our scientific everyday sense of reality."

In the News ...

Study shows compassion meditation changes the brain PhysOrg - March 27, 2008

- Can we train ourselves to be compassionate? A new study suggests the answer is yes. Cultivating compassion and kindness through meditation affects brain regions that can make a person more empathetic to other peoples' mental states, say researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Published March 25 in the Public Library of Science One, the study was the first to use functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to indicate that positive emotions such as loving-kindness and compassion can be learned in the same way as playing a musical instrument or being proficient in a sport. The scans revealed that brain circuits used to detect emotions and feelings were dramatically changed in subjects who had extensive experience practicing compassion meditation.

The research suggests that individuals ‹ from children who may engage in bullying to people prone to recurring depression ‹ and society in general could benefit from such meditative practices, says study director Richard Davidson, professor of psychiatry and psychology at UW-Madison and an expert on imaging the effects of meditation. Davidson and UW-Madison associate scientist Antoine Lutz were co-principal investigators on the project.

The study was part of the researchers' ongoing investigations with a group of Tibetan monks and lay practitioners who have practiced meditation for a minimum of 10,000 hours. In this case, Lutz and Davidson worked with 16 monks who have cultivated compassion meditation practices. Sixteen age-matched controls with no previous training were taught the fundamentals of compassion meditation two weeks before the brain scanning took place.

"Many contemplative traditions speak of loving-kindness as the wish for happiness for others and of compassion as the wish to relieve others' suffering. Loving-kindness and compassion are central to the Dalai Lama's philosophy and mission," says Davidson, who has worked extensively with the Tibetan Buddhist leader. "We wanted to see how this voluntary generation of compassion affects the brain systems involved in empathy."

Various techniques are used in compassion meditation, and the training can take years of practice. The controls in this study were asked first to concentrate on loved ones, wishing them well-being and freedom from suffering. After some training, they then were asked to generate such feelings toward all beings without thinking specifically about anyone.

Each of the 32 subjects was placed in the fMRI scanner at the UW-Madison Waisman Center for Brain Imaging, which Davidson directs, and was asked to either begin compassion meditation or refrain from it. During each state, subjects were exposed to negative and positive human vocalizations designed to evoke empathic responses as well as neutral vocalizations: sounds of a distressed woman, a baby laughing and background restaurant noise.

"We used audio instead of visual challenges so that meditators could keep their eyes slightly open but not focused on any visual stimulus, as is typical of this practice," explains Lutz. The scans revealed significant activity in the insula - a region near the frontal portion of the brain that plays a key role in bodily representations of emotion - when the long-term meditators were generating compassion and were exposed to emotional vocalizations. The strength of insula activation was also associated with the intensity of the meditation as assessed by the participants.

"The insula is extremely important in detecting emotions in general and specifically in mapping bodily responses to emotion - such as heart rate and blood pressure - and making that information available to other parts of the brain," says Davidson, also co-director of the Health Emotions Research Institute. Activity also increased in the temporal parietal juncture, particularly the right hemisphere. Studies have implicated this area as important in processing empathy, especially in perceiving the mental and emotional state of others. "Both of these areas have been linked to emotion sharing and empathy," Davidson says. "The combination of these two effects, which was much more noticeable in the expert meditators as opposed to the novices, was very powerful."

The findings support Davidson and Lutz's working assumption that through training, people can develop skills that promote happiness and compassion. "People are not just stuck at their respective set points," he says. "We can take advantage of our brain's plasticity and train it to enhance these qualities." The capacity to cultivate compassion, which involves regulating thoughts and emotions, may also be useful for preventing depression in people who are susceptible to it, Lutz adds. "Thinking about other people's suffering and not just your own helps to put everything in perspective," he says, adding that learning compassion for oneself is a critical first step in compassion meditation.

The researchers are interested in teaching compassion meditation to youngsters, particularly as they approach adolescence, as a way to prevent bullying, aggression and violence. "I think this can be one of the tools we use to teach emotional regulation to kids who are at an age where they're vulnerable to going seriously off track," Davidson says.

Compassion meditation can be beneficial in promoting more harmonious relationships of all kinds, Davidson adds. "The world certainly could use a little more kindness and compassion," he says. "Starting at a local level, the consequences of changing in this way can be directly experienced." Lutz and Davidson hope to conduct additional studies to evaluate brain changes that may occur in individuals who cultivate positive emotions through the practice of loving-kindness and compassion over time.

Source: University of Wisconsin-Madison

Brain Scans Reveal Why Meditation Works Live Science - June 30, 2007

- If you name your emotions, you can tame them, according to new research that suggests why meditation works. Brain scans show that putting negative emotions into words calms the brain's emotion center. That could explain meditation¹s purported emotional benefits, because people who meditate often label their negative emotions in an effort to let them go.

Psychologists have long believed that people who talk about their feelings have more control over them, but they don't know why it works. UCLA psychologist Matthew Lieberman and his colleagues hooked 30 people up to functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machines, which scan the brain to reveal which parts are active and inactive at any given moment. They asked the subjects to look at pictures of male or female faces making emotional expressions. Below some of the photos was a choice of words describing the emotion - such as 'angry' or 'fearful' - or two possible names for the people in the pictures, one male name and one female name.

When presented with these choices, the subjects were asked to pick the most appropriate emotion or gender-appropriate name to fit the face they saw. When the participants chose labels for the negative emotions, activity in the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex region - an area associated with thinking in words about emotional experiences - became more active, whereas activity in the amygdala, a brain region involved in emotional processing, was calmed.

By contrast, when the subjects picked appropriate names for the faces, the brain scans revealed none of these changes - indicating that only emotional labeling makes a difference. "In the same way you hit the brake when you¹re driving when you see a yellow light, when you put feelings into words, you seem to be hitting the brakes on your emotional responses," Lieberman said of his study, which is detailed in the current issue of Psychological Science. In a second experiment, 27 of the same subjects completed questionnaires to determine how ³mindful² they are.

Meditation and other 'mindfulness' techniques are designed to help people pay more attention to their present emotions, thoughts and sensations without reacting strongly to them. Meditators often acknowledge and name their negative emotions in order to let them go. When the team compared brain scans from subjects who had more mindful dispositions to those from subjects who were less mindful, they found a stark difference - the mindful subjects experienced greater activation in the right ventrolateral prefrontral cortex and a greater calming effect in the amygdala after labeling their emotions. "These findings may help explain the beneficial health effects of mindfulness meditation, and suggest, for the first time, an underlying reason why mindfulness meditation programs improve mood and health," said David Creswell, a UCLA psychologist who led the second part of the study, which will be detailed in Psychosomatic Medicine.

Areas of the brain activated during meditation - Tracing the Synapses of Spirituality

June 17, 2001 - Washington Post

In Philadelphia, a researcher discovers areas of the brain that are activated during meditation. At two other universities in San Diego and North Carolina, doctors study how epilepsy and certain hallucinogenic drugs can produce religious epiphanies. And in Canada, a neuroscientist fits people with magnetized helmets that produce "spiritual" experiences for the secular. The work is part of a broad new effort by scientists around the world to better understand religious experiences, measure them, and even reproduce them. Using powerful brain imaging technology, researchers are exploring what mystics call nirvana, and what Christians describe as a state of grace. Scientists are asking whether spirituality can be explained in terms of neural networks, neurotransmitters and brain chemistry.

What creates that transcendental feeling of being one with the universe? It could be the decreased activity in the brain's parietal lobe, which helps regulate the sense of self and physical orientation, research suggests. How does religion prompt divine feelings of love and compassion? Possibly because of changes in the frontal lobe, caused by heightened concentration during meditation. Why do many people have a profound sense that religion has changed their lives? Perhaps because spiritual practices activate the temporal lobe, which weights experiences with personal significance.

"The brain is set up in such a way as to have spiritual experiences and religious experiences," said Andrew Newberg, a Philadelphia scientist who authored the book "Why God Won't Go Away." "Unless there is a fundamental change in the brain, religion and spirituality will be here for a very long time. The brain is predisposed to having those experiences and that is why so many people believe in God."

The research may represent the bravest frontier of brain research. But depending on your religious beliefs, it may also be the last straw. For while Newberg and other scientists say they are trying to bridge the gap between science and religion, many believers are offended by the notion that God is a creation of the human brain, rather than the other way around. "It reinforces atheistic assumptions and makes religion appear useless," said Nancey Murphy, a professor of Christian philosophy at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, Calif. "If you can explain religious experience purely as a brain phenomenon, you don't need the assumption of the existence of God."

Some scientists readily say the research proves there is no such thing as God. But many others argue that they are religious themselves, and that they are simply trying to understand how our minds produce a sense of spirituality.

Newberg, who was catapulted to center stage of the neuroscience-religion debate by his book and some recent experiments he conducted at the University of Pennsylvania with co-researcher Eugene D'Aquili, says he has a sense of his own spirituality, though he declined to say whether he believed in God because any answer would prompt people to question his agenda. "I'm really not trying to use science to prove that God exists or disprove God exists," he said. Newberg's experiment consisted of taking brain scans of Tibetan Buddhist meditators as they sat immersed in contemplation. After giving them time to sink into a deep meditative trance, he injected them with a radioactive dye. Patterns of the dye's residues in the brain were later converted into images.

Newberg found that certain areas of the brain were altered during deep meditation. Predictably, these included areas in the front of the brain that are involved in concentration. But Newberg also found decreased activity in the parietal lobe, one of the parts of the brain that helps orient a person in three-dimensional space. "When people have spiritual experiences they feel they become one with the universe and lose their sense of self," he said. "We think that may be because of what is happening in that area ‚ if you block that area you lose that boundary between the self and the rest of the world. In doing so you ultimately wind up in a universal state."

Across the country, at the University of California in San Diego, other neuroscientists are studying why religious experiences seem to accompany epileptic seizures in some patients. At Duke University, psychiatrist Roy Mathew is studying hallucinogenic drugs that can produce mystical experiences and have long been used in certain religious traditions.

Could the flash of wisdom that came over Siddhartha Gautama - the Buddha - have been nothing more than his parietal lobe quieting down? Could the voices that Moses and Mohammed heard on remote mountain tops have been just a bunch of firing neurons - an illusion? Could Jesus's conversations with God have been a mental delusion?

Newberg won't go so far, but other proponents of the new brain science do. Michael Persinger, a professor of neuroscience at Laurentian University in Sudbury, Ontario, has been conducting experiments that fit a set of magnets to a helmet-like device. Persinger runs what amounts to a weak electromagnetic signal around the skulls of volunteers. Four in five people, he said, report a "mystical experience, the feeling that there is a sentient being or entity standing behind or near" them. Some weep, some feel God has touched them, others become frightened and talk of demons and evil spirits. "That's in the laboratory," said Persinger. "They know they are in the laboratory. Can you imagine what would happen if that happened late at night in a pew or mosque or synagogue?" His research, said Persinger, showed that "religion is a property of the brain, only the brain and has little to do with what's out there." Those who believe the new science disproves the existence of God say they are holding up a mirror to society about the destructive power of religion. They say that religious wars, fanaticism and intolerance spring from dogmatic beliefs that particular gods and faiths are unique, rather than facets of universal brain chemistry.

James Austin, a neurologist, began practicing Zen meditation during a visit to Japan. After years of practice, he found himself having to re-evaluate what his professional background had taught him. "It was decided for me by the experiences I had while meditating," said Austin, author of the book "Zen and the Brain" and now a philosophy scholar at the University of Idaho. "Some of them were quickenings, one was a major internal absorption ‚ an intense hyper-awareness, empty endless space that was blacker than black and soundless and vacant of any sense of my physical bodily self. I felt deep bliss. I realized that nothing in my training or experience had prepared me to help me understand what was going on in my brain. It was a wake-up call for a neurologist."

Austin's spirituality doesn't involve a belief in God ‚ it is more in line with practices associated with some streams of Hinduism and Buddhism. Both emphasize the importance of meditation and its power to make an individual loving and compassionate ‚ most Buddhists are disinterested in whether God exists. But theologians say such practices don't describe most people's religiousness in either eastern or western traditions.

"When these people talk of religious experience, they are talking of a meditative experience," said John Haught, a professor of theology at Georgetown University. "But religion is more than that. It involves commitments and suffering and struggle ‚ it's not all meditative bliss. It also involves moments when you feel abandoned by God." "Religion is visiting widows and orphans," he said. "It is symbolism and myth and story and much richer things. They have isolated one small aspect of religious experience and they are identifying that with the whole of religion."

Belief and faith, argue believers, are larger than the sum of their brain parts: "The brain is the hardware through which religion is experienced," said Daniel Batson, a University of Kansas psychologist who studies the effect of religion on people. "To say the brain produces religion is like saying a piano produces music." At the Fuller Theological Seminary's school of psychology, Warren Brown, a cognitive neuropsychologist, said, "Sitting where I'm sitting and dealing with experts in theology and Christian religious practice, I just look at what these people know about religiousness and think they are not very sophisticated. They are sophisticated neuroscientists, but they are not scholars in the area of what is involved in various forms of religiousness."

At the heart of the critique of the new brain research is what one theologian at St. Louis University called the "nothing-butism" of some scientists ‚ the notion that all phenomena could be understood by reducing them to basic units that could be measured. And finally, say believers, if God existed and created the universe, wouldn't it make sense that he would install machinery in our brains that would make it possible to have mystical experiences? "Neuroscientists are taking the viewpoints of physicists of the last century that everything is matter," said Mathew, the Duke psychiatrist. "I am open to the possibility that there is more to this than what meets the eye. I don't believe in the omnipotence of science or that we have a foolproof explanation."

No comments:

Post a Comment